LNG, or liquefied natural gas, is natural gas that has been super-cooled (−162°C) to a liquid state for easier storage and transportation. Natural gas has 600 times less volume in liquid form than gaseous, and LNG can be transported by ship, truck or rail to places traditional natural gas pipelines cannot reach, or can even be used as a fuel directly. In general, the gas is first liquefied in its country of origin, then transported via ships and re-gasified at the destination, before being fed into existing gas grids and pipelines.

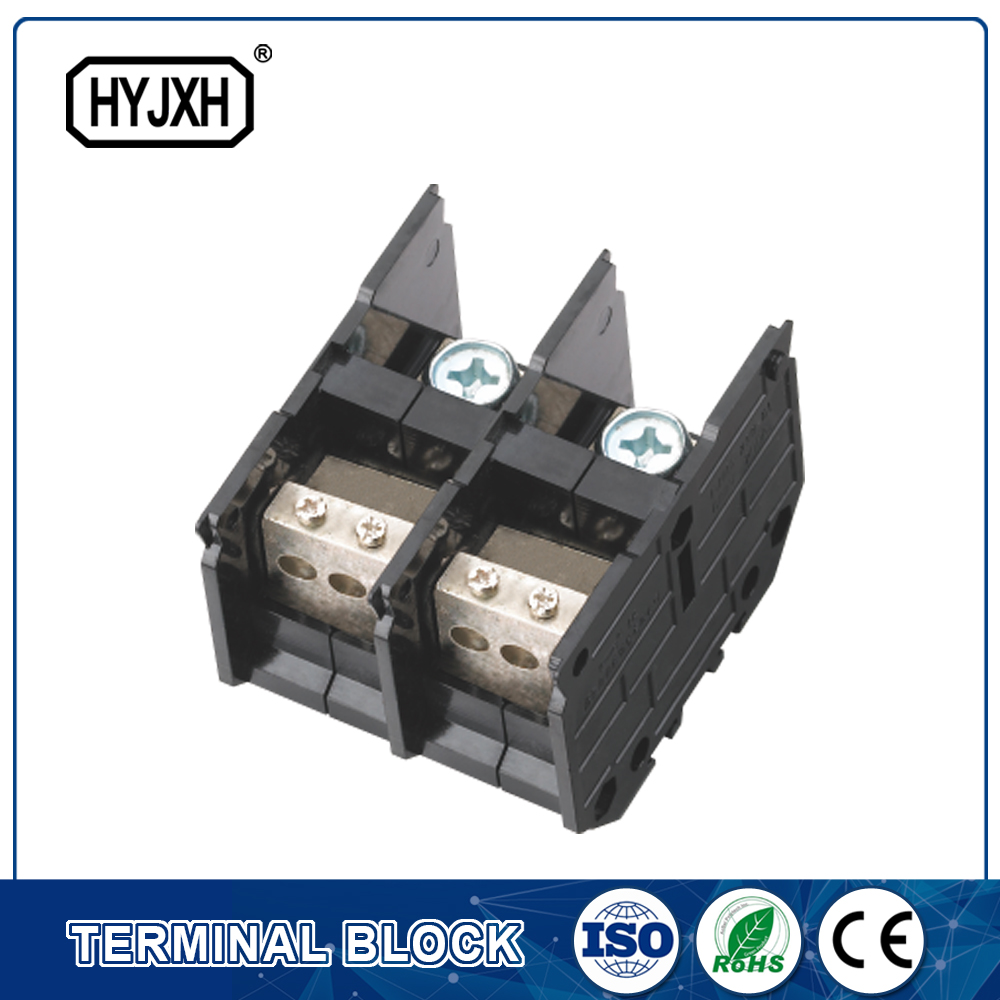

Compared to other fossil fuels, natural gas emits the least amount of carbon dioxide when burned, prompting many countries to see it as a potential “bridge fuel” between dirtier fossil fuels and carbon-free energy sources. However, natural gas is primarily composed of methane, itself a powerful greenhouse gas, and the rate of methane leakage in natural gas production, transport and storage is still hotly debated. Combination Type Terminal Block

The coronavirus pandemic caused a global demand shock in 2020, which impacted gas production. Subsequently, supply could not keep up with rebounding demand during the economic recovery, leading to a gas crisis that hit Europe hardest, with prices reaching record highs.

Russia’s war against Ukraine exacerbated the crisis from early 2022, as sanctions, other political action and eventually sabotage of the Nord Stream projects led to supply cuts and eventually a stop of direct pipeline deliveries from Russia to Germany.

Dominated by surging LNG demand in Europe in response to sharp cuts in pipeline gas supply from Russia, g lobal LNG trade is set to grow by 5 percent in 2022, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). However, this is less than the 2016-2021 average of 8 percent , it said.

United States, Qatar and Russia are the world’s biggest exporters of LNG, said IEA. The U.S. has been the main driver of LNG growth in recent years. Looking ahead, the U.S. and Qatar are expected to engage in a two-horse race for dominance in the global LNG market, reported Bloomberg. Other major exporters include Australia, Malaysia, Nigeria, Indonesia, Algeria, Russia, Trinidad & Tobago, Oman and Papua New Guinea.

China was the world’s biggest LNG-importing country in 2021, followed by Japan. Taken together, European countries also import a sizeable share. In 2020, Europe was responsible for a quarter of global inter-regional LNG trade.

In 2021, 13 EU countries imported a total of 80 billion cubic metres of LNG, and LNG imports made up 20 percent of total extra-EU gas imports in 2021. The bulk of natural gas is imported via pipeline, mostly from Russia and Norway. Around 10 percent of the EU's gas needs are currently met by domestic production and the share is set to decrease over the coming years.

The biggest LNG importers in the EU were Spain (21.3 bcm), France (18.3 bcm), Italy (9.3 bcm), the Netherlands (8.7 bcm) and Belgium (6.5 bcm).

While Europe’s LNG terminals have been underutilised on an annual average, Reuters reported that most operated at full capacity in February 2022. Spain has the continent's biggest capacity – which is not yet used to full capacity – but has only limited pipeline connections to the rest of the continent.

The European Commission says LNG can boost the EU's gas supply diversity and therefore improve energy security. In July 2018, European Commission President Jean-Claude Junker pledged that the bloc would import significant amounts of LNG from the U.S. as a concession to cool a potential trade war. While largely a matter of business rather than politics, exports from the U.S. to Europe have indeed increased every year since then. In 2021 LNG exports to the EU recorded the highest volume, reaching more than 22 billion cubic meters, with an estimated value of 12 billion euros.

In March 2022, the U.S. and the EU said that the U.S. would scale up LNG exports to Europe to 50 bcm per year starting in 2023. However, if the continent aims to replace a sizable chunk of current Russian pipeline gas with LNG from different sources, the import infrastructure is insufficient.

Due to the war in Ukraine, "we’re seeing right now a flurry of new announced projects across EU member states,” Simon Dekeyrel, a climate and energy analyst at the European Policy Centre , told Energy Monitor. “But a big LNG import terminal takes around five years to build and come online” and require "very substantial investments".

Germany is one of the world’s biggest gas importers and sources about 95 percent of its consumption from abroad. More than one quarter of Germany’s energy demand was covered by natural gas in 2021, the second most important energy source in the mix after oil. Russia (around 55 percent), Norway and the Netherlands were the most important source countries. Gas is currently imported to Germany only via pipelines.

Germany does not have its own regasification terminals for LNG and imports enter through neighbouring countries’ terminals, especially Belgium and the Netherlands. Germany also receives some LNG via road freight.

For years, it appeared there was no economic case for direct LNG imports to Germany, since the country is so well-connected for receiving gas through pipelines from neighbouring countries and because European LNG import capacities were heavily underutilised. Critics have also argued that LNG imports are more expensive than gas delivered via pipeline.

This had caused the debate about a domestic LNG terminal to largely subside in recent years, and plans were plagued by delays and uncertainty. However, the wish to lessen reliance on Russia in light of president Vladimir Putin's war against Ukraine, Russia stopping direct pipeline deliveries, and high gas prices have revived discussions.

Germany has since gone full steam ahead on expanding its import infrastructure.

Days after Russia invaded Ukraine, chancellor Scholz announced Germany will build two domestic import terminals. Economy and climate minister Robert Habeck said this is necessary to “govern energy supply on our own state territory and guarantee sovereignty.” The German government quickly announced it will co-fund with a 50 percent stake the terminal project in Brunsbüttel. To speed up the permit and construction process, the government introduced an 'LNG Acceleration Act'. It allows the licensing authorities, under certain conditions, to temporarily waive some procedural requirements, especially in the area of environmental impact assessment.

In addition to one or more fixed onshore terminals, the German government plans to lease five so-called Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRU) in the short term, two of which could be installed as early as the winter 2022/2023 (plans for the fifth were announced in September 2022). By July, the government had decided that the ports of Wilhelmshaven and Brunsbüttel, Stade and Lubmin would host the terminals. A sixth floating terminal with government support is to be installed in Hamburg. A private consortium would establish a seventh terminal in Lubmin (see details below), later another. Due to the fallout of Russia’s war against Ukraine there is international competition for FSRUs, of which there are currently just under 50 worldwide, according to German news service Tagesspiegel Background.

The chancellor emphasised that the fixed onshore terminals could eventually be converted to handle climate-friendly gases. “An LNG terminal that receives gas today can also receive green hydrogen tomorrow,” said Scholz. This is in line with plans by the economy ministry, but also subject to criticism, because it is not clear what a later conversion of the terminals would entail.

There are other reasons that could make more autonomy in the gas sector attractive for Germany. Shipping companies could need LNG as an alternative to the CO2-intensive fuel they use at the moment and LNG could play a growing role in their efforts to reduce emissions in the freight industry. If Germany’s harbours want to remain internationally competitive, they might need to supply ships with LNG in the future, German business publication Handelsblatt wrote in 2018.

There had been three major German LNG terminal projects going through the planning process for several years: Scholz in his speech mentioned Brunsbüttel (German LNG Terminal) at the Elbe river near the North Sea, and a competing location in the city of Wilhelmshaven (LNG Terminal Wilhelmshaven GmbH). The third long-term project is planned in Stade (Hanseatic Energy Hub), near Hamburg. With the government getting involved, the projects have changed slightly.

By December 2022, there had not been a final investment decision on any of the fixed onshore terminals, reported Table.Media.

In Brunsbüttel, in the northernmost state of Schleswig-Holstein, a consortium named German LNG Terminal plans to build a regasification facility with a capacity of 8-10 billion cubic metres (bcm). The project had been delayed, but the government in March 2022 said it will co-fund it with a 50 percent stake through the development bank KfW. The project is a joint venture between KfW, Dutch government-owned Gasunie (40%) and RWE (10%), and will be operated by Gasunie. Shell has said it will make a long-term booking of “a substantial part” of the terminal’s capacity. The regional government aims to change regulation to speed up the construction process. It could be operational by 2026 if plans can be sped up. "Schleswig-Holstein will do everything in its power to ensure that the chancellor's clear commitment to the construction of an LNG terminal in Brunsbüttel is taken forward swiftly," state premier Daniel Günther (CDU) has said. The project has in the past been a target of environmental protests.

Floating terminals (some with plans for later fixed onshore terminals):

Several reports have criticised the size of German LNG plans. These are “massively oversized” and state involvement means that taxpayer money is used for what could eventually become stranded assets, said a report by think tank NewClimate Institute in December 2022 . In another report presented in July, the DUH and the Heinrich Böll Foundation said Europe should avoid “gigantic overcapacities” by coordinating the development of LNG infrastructure.

In general, there is considerable opposition to a German LNG terminal from environmental organisations. Environmental Action Germany (DUH) called Scholz’s decision “premature” and said such installations create more dependence on fossil energy.

In April, DUH criticised plans for an import terminal in Stade, arguing that it will not help with the current energy crisis and will harm the climate. “Despite all the claims to the contrary by the developer and politicians, the terminal can only be used for the import of fossil natural gas,” said managing director Sascha Müller-Kraenner. This means that it will not contribute to the energy transition, but will cement our dependence on climate-damaging fuels for decades to come.

A recent report by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) concluded that Germany does not need its own import terminals. The researchers warned the projects do not “make sense due to the long construction times and the sharp decline in natural gas demand in the medium term,” and warned of stranded assets.

Dresdener Str. 15 10999 Berlin, Germany

Researching a story? Drop CLEW a line or give us a call for background material and contacts.

Terminal Block Connector Journalism for the energy transition